Author: Professor Pieter Steyn

Source: PM World Journal – Vol. II, Issue III – March 2013

www.pmworldjournal.net

Introduction

Effective and efficient management of the Supply Chain Portfolio is widely regarded as the key to optimal organisational performance. How to achieve this has remained a complex challenge to executives and senior management of organisations in the private and public sectors. Programme management has moved beyond its initial application of managing cross-functional portfolios of projects. Organisations that follow a project driven business model do projects for external customers on the basis of successful tenders (bids). They have been structuring their project management processes into cross-functional matrixes for many decades. Stated differently, they have since the 1970s been arranging their project driven business model supply chain processes into cross-functional matrixes to optimise organisational performance. This was the beginning of the demise of bureaucratic structures and paradigms that eventually led to the modern day knowledge-based learning approach of leading and managing the organisation.

Stock and Lambert (2001) describe Supply Chain management as a highly interactive, complex systems approach that requires simultaneous consideration of many trade-offs. Supply Chain management integrates key cross-functional business processes from suppliers to end users and provides products, services and information that add value for customers and other stakeholders. They identify the structural dimensions of the Supply Chain Portfolio as the participating members, the cross-functional processes of the Supply Chain, and the different types of process links across the Supply Chain. They correctly identify executive support, leadership excellence, commitment to change, and empowerment as key requirements for successful Supply Chain management, and regard information as a key enabler of Supply Chain Portfolio integration. They assert that, due to the dynamic nature of modern organisations, leadership and management should regularly monitor and evaluate the performance of the Supply Chain. They regard it as imperative that performance goals are met, and failing so, Supply Chain alternatives are evaluated and change implemented. However, they do not propose a synergetic structural model for managing the abovementioned.

Steyn (2003, 2010 and 2012) avers that the abovementioned is virtually impossible to achieve in bureaucratic organisations and the challenge is for organisations to transform to learning organisation paradigms and structures. Garvin (1993) provides the following definition of a learning organisation: “A learning organisation is an organisation skilled at creating, acquiring and transferring knowledge and at modifying its behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights”. He asserts that to stay competitive in the new economy, organisations must strive to move away from bureaucratic practices towards becoming learning organisations that are far more agile and flexible. Steyn (2001, 2003, and 2010) proposes that organisations shape all their cross-functional portfolios into various programme structures, some processes serving internal customers and others external customers. In addition to the project related programme structures of the Strategic Transformation Portfolio, Continuous Improvement Portfolio, Capital Expenditure Portfolio, and Virtual Network of Partners Portfolio, they should also shape the Supply Chain Portfolio’s cross-functional processes into a programme management structure, or structures depending on the business model adopted. Moreover, a management structure consisting of project-, process-, programme-, and portfolio managers must be created to bring synergy, including a Chief Portfolio Officer (CPO) as part of the executive.

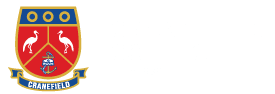

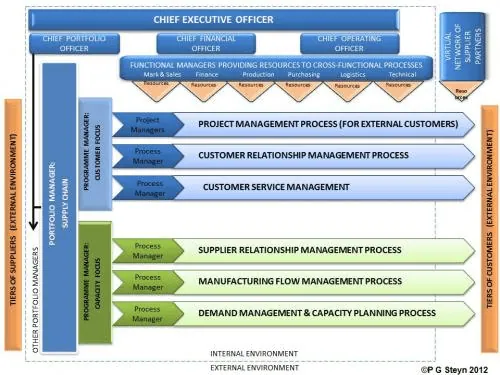

As shown in Figure 1 (from Steyn, 2010) the Supply Chain Portfolio is an integral part of the cross-functional programme structures of learning organisations. The programme configurations are not mutually exclusive. They support each other in an integrated way and the strategic picture is linked to the operational activities. The major organisational benefits of strategic importance delivered by the individual programme configurations vary from effectiveness, efficiency, and both effectiveness and efficiency. Moreover, benefits of strategic importance of the deliverables of the various cross-functional processes must be measured by utilising appropriate key performance indicators (KPIs) that are linked to critical success factors (CSFs) in a balanced scorecard. This should be followed by appraisals performed by senior management and the executive leadership to determine whether organisational benefits of strategic importance accrue to a satisfactory degree.. If not, the situation must be reviewed with the aim of correcting it through continuous improvement projects.

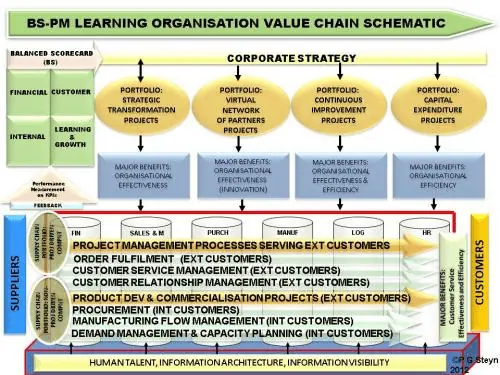

According to Steyn (2010) the portfolios, including the Supply Chain Portfolios, are arranged into different programme structures each with its own portfolio manager and support staff as illustrated in Figure 2. It is essential that it includes a Chief Portfolio Officer (CPO) at the executive level of the organisation to enhance cross-functional leadership and management of the knowledge-based learning organisation.

Programme Structures for Project Driven-, Non-project Driven, and Hybrid Business Models

Depending on its business model organisations can be structured as project driven, non-project driven, or hybrid. Hybrid means that the organisation has both a project driven, as well as a non-project driven component in its Supply Chain. As alluded to earlier in the article, project driven organisations have been structuring their project supply chain in a matrix as early as the 1970s. It was only at the turn of the century that researchers such as Lambert, et al (1998 and 2001), Steyn (2001), and Croxton, et al (2001) started advocating that supply chain processes of the non-project driven business model organisations should also be structured cross-functionally. Steyn (2003, 2010 and 2012) avers that the non-project driven business model Supply Chain Portfolio consists of seven key cross-functional business processes categorised as the “customer component” and “capacity component“. Moreover, the seven key cross-functional processes apply to the project driven business model organisation as well, albeit in a different form. The seven key cross-functional processes are the following:

- Customer relationship management (CRM).

- Customer service management (CSM).

- Order fulfilment.

- Product development and commercialisation.

- Supplier relationship management (procurement).

- Demand management and capacity planning.

- Manufacturing flow management.

The manner in which the supply chain is structured in an organisation that adopts a non-project driven business model, as opposed to one that adopts a project driven business model, varies as described below.

Programme structures for non-project driven organisations

Non-project driven organisations generate income (revenue) by selling products and services to external customers. In non-project driven organisations the cross functional project management process serving external customers, as shown in Figure 1, does not exist. Non-project driven organisations are not in the business of doing projects.

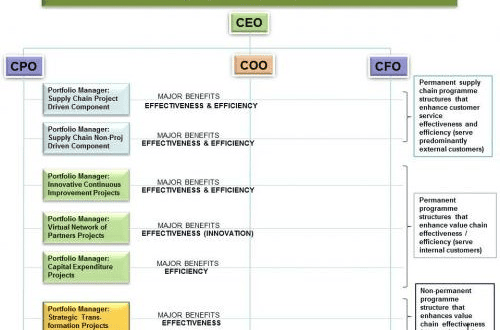

The value chain schematic for the non-project driven business model organisation is shown in Figure 3. The supply chain includes the four “customer component” business processes, i.e., Customer Relationship Management (CRM), Customer Service Management (CSM), Order Fulfilment, and Product Development and Commercialisation that serve external customers. The remaining three business processes, i.e, Supplier Relationship Management (Procurement), Demand Management and Capacity Planning, and Manufacturing Flow Management serve internal customers and constitute the “capacity component”, which supports the four cross-functional “customer component” business processes.

Of the seven cross functional supply chain business processes present in the non-project driven business model organisation, only Product Development and Commercialisation is a project-based business process. The programme management structure for the non-project driven business model organisation, which include portfolio managers and importantly a Chief Portfolio Officer (CPO), is shown in Figure 4.

Programme Structures for Project Driven Organisations

Project driven organisations are unique. To win orders they tender on RFPs (requests for proposals) received from the external customers. When successful in their tenders (bids) they generate income (revenue) by doing the projects for those external customers. As stated in the opening paragraph of this article, they have for decades created and utilised cross-functional (matrix) project management processes in their Supply Chain Portfolio to achieve optimal organisational performance.

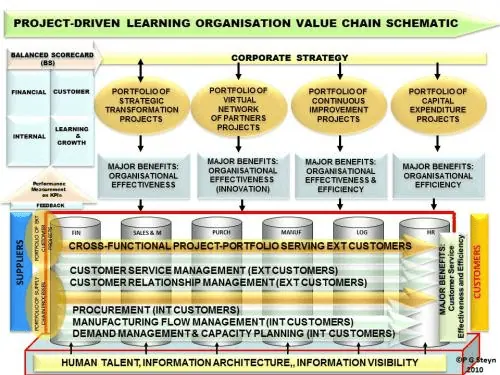

Steyn (2010 and 2012) purports that in organisations adopting the pure project driven business model in modern day learning organisations, the cross-functional Order Fulfilment, as well as, the Product Development and Commercialisation supply chain processes become an integral part of the matrix project management activities performed by the project team members. In project work the project managers are responsible for the design of the deliverables and compile the schedules that fulfil the customers’ orders. Hence, the “customer component” of the pure project driven business model organisation’s Supply Chain consists of the project work plus the two abovementioned cross-functional business processes. Similar to the non-project driven situation, the remaining three supply chain processes, i.e., Supplier Relationship Management (Procurement), Demand Management and Capacity Planning, and Manufacturing Flow Management constitute the “capacity component”, which supports the “customer component” supply chain processes. The value chain schematic for the project driven business model is shown in Figure 5.

The programme management structure for the project driven business model, which again include portfolio managers and importantly a Chief Portfolio Officer (CPO), is shown in Figure 6.

Programme Structures for Hybrid Organisations

Hybrid organisations are plentiful and have both project driven and non-project driven components in its Supply Chain Portfolio as described above. Steyn (2010) asserts that to enhance value chain effectiveness and efficiency project driven, non-project driven, and hybrid organisations need to adopt Continuous Improvement-, Capital Expenditure-, and Virtual Network of Partners Portfolios as programme structures. Moreover, when the need arises they must establish a Strategic Transformation Portfolio programme structure to analyse, develop and implement emergent strategy.

Conclusion

To conclude it is appropriate to recap on some important aspects regarding project and programme management processes and teams. A process is continuous, while a project is finite. A project life cycle has four phases, namely conceptualization, development, implementation and termination, and is often performed as part of a programme. Programme management is a continuous general management activity. Key differences exist between an individual project and a programme. A project has a predetermined fixed objective, whereas programmes have more flexible objectives that can change over time. In all programmes the organisational benefits are delivered continuously into the future. In a project the organisational benefits are delivered through a single initiative and short cycle.

The first and foremost task in a programme is to identify its strategic purpose. The strategic purpose immediately links to the balanced scorecard approach. Based on the strategic themes chosen by executive leadership, critical success factors and key performance indicators, together with their relative priority, are identified. Strategies are developed and described, based on the strategic intent of executive leadership. Portfolio and programme managers adopt a flexible approach to organisational goals, and focus on doing the right things. The former aims to achieve predetermined outcomes utilising the least possible resources, while programmes aim to utilise the best possible resources to achieve maximum organisational benefits of strategic importance. Portfolio and programme manager play a facilitative role, concentrating on the strategic organisational objectives to be achieved.

For optimal organisational performance it is imperative that the programme structures of the different portfolios operate in synergy, irrespective of the business model adopted by an organisation. Coordinating and integrating the activities of the Supply Chain Portfolio with that of other cross-functional portfolios is a key success factor. Sound structuring, leading and managing of the supply chain programme architecture in the flexible and agile culture of a learning organisation paradigm, are important characteristics alluded to by Steyn (2012).

Bibliography:

Croxton K, García-Dastugue S, Lambert D, and Rogers D, 2001, “The Supply Chain Management Processes,” The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 12, No. 2.

Garvin, D A, 1993, “Building a Learning Organization”, Harvard Business Review, July-Aug.

Lambert D, Cooper M, and Pagh J, 1998, “Supply Chain Management Implementation Issues and Research Opportunities”, The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 9, No. 2.

Steyn P G, 2012, “Sustainable Strategic Supply Chain Leadership & Management”, PM World Journal, December, Vol. I, Issue V.

Steyn P G, 2010, “The Need for a Chief Portfolio Officer (CPO) in Organisations”, PM World Today, July, Vol XII, Issue VII.

Steyn P G, 2003, “The Balanced Scorecard Programme Management System”, Proceedings of the 17th IPMA Global Congress on Project Management, Berlin, Germany.

Steyn P G, 2001, “Managing Organisations through Projects and Programmes: The Modern General Management Approach”, Management Today, April, Vol 17, No 3.

Stock, J R and Lambert, D M, 2001, “Strategic Logistics Management”, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, McGraw-Hill International Edition.